“We’re going to shift this number from 19% to 25%.” If this figure is the proportion of employees from a specific minority ethnic group in the total workforce, it is admirable, of course but does it mean much? It doesn’t sound much, really, does it? That might be the forgivable reaction to Norton Rose Fulbright’s (NRF) recent announcement of new diversity targets for its UK operation.

Forgivable, but maybe not right. In this blog, I want to go behind these numbers to draw out the implications for NRF’s recruitment in the UK over the next half-decade. In doing so, I hope I can demonstrate that NRF deserve praise for their commitment to targets that might be a lot harder to achieve than it first appears. (For the avoidance of all doubt, this blog is only about NRF in the UK.)

Diversity has been close to the top of UK law firms’ agendas for most of the last decade. The killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis earlier this year became a new tipping point in race relations, not only in the US, but also in other Western countries. It added some new urgency not only to the need to address systemic racism and bias in our society and its institutions, but also to the speed with which we need to achieve visible results.

NRF is not the only firm to have made public commitments to hard diversity and inclusion (D&I) targets in the UK, as the Law Society Gazette recently reported. But its figures were sufficiently detailed (with respect to both quantity and timeframe) to make them worthy of further analysis.

I want to concentrate on two of the targets:

- to grow the proportion of the UK workforce that is BAME from its current 19% to 25% by 2025.

- to grow the proportion of the UK partnership that is BAME from its current 8% to 15% in the same time frame.

(I know that the term “BAME” is not accepted by all who fall within its current public definition, and there is considerable debate about the value of grouping a number of heterogeneous non-White ethnicities into a single category. So, my apologies if my use of the term offends anyone, but it is a term in general use, and it is the term NRF have used to frame their targets).

We know that NRF has, globally, 3,700 legal staff and a total workforce of 7,000. In the UK they have (December, 2019 figures):

- a total workforce of 1,273; and

- 153 partners.

I have made the simplifying assumption that “now” means the end of 2020 and 2025 means the end of 2025 – so a five-year target.

So, let’s start with the total UK workforce target. There are three broad strategies to meet a future distribution target that is different to today’s distribution. The first two look at getting there immediately, the third does it over a period of time.

- reduce the total number of staff, by reducing the number of non-BAME employees till the proportions match the target.

- keep the total number of staff the same, but adjust the current proportions by a mixture of increasing BAME numbers and reducing non-BAME numbers.

- gradually change the proportions by disproportionate recruitment of BAME and non-BAME staff until the proportions coincide with the targets. This can be by the target date or in advance of it.

It’s obvious that NRF will have no interest in either strategy #1 or #2 (both involve the letting go of existing staff), and will be going for #3. But for completeness, let’s look at the implications of strategies #1 and #2.

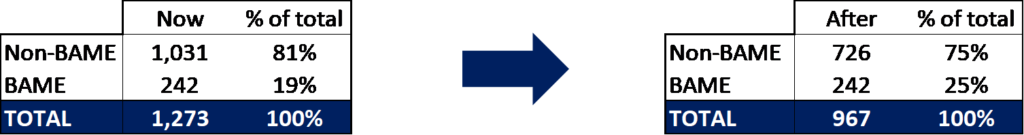

Strategy #1

A one-time adjustment to meet the ethnicity targets would require a reduction in non-BAME numbers from 1,031 to 726 or a reduction of 306 in non-BAME numbers. (Note: all the charts contain rounded figures….)

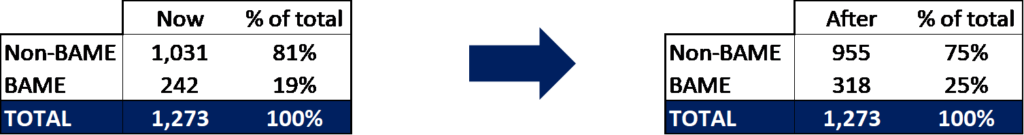

Strategy #2

A one-time adjustment to meet the ethnicity targets without any reduction in overall numbers would require a reduction in non-BAME numbers from 1,031 to 955 and an increase in BAME numbers from 242 to 318. This is a reduction of 76 in non-BAME numbers, with an equal increase in BAME numbers.

It’s fairly obvious that neither strategy is what NRF is pursuing, or would ever pursue. That’s why the target has a five-year time frame. But these numbers give an indication of the scale of the shift that NRF is contemplating.

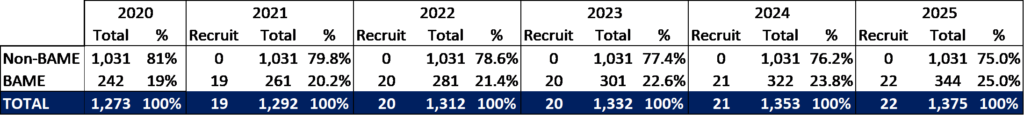

Strategy #3 – minimum

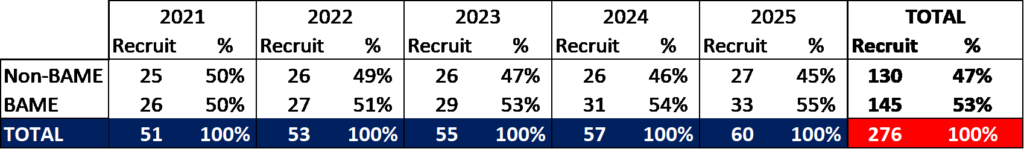

So, let’s look at what we might call the “minimum version” of strategy #3. This is the strategy that recruits only BAME staff until the figures are in the correct proportions, aiming to reach this point at the five-year marker. Let’s also assume that the change is linear (equal annual steps towards the target). Here’s what the year end figures would look like.

Under this “minimum” strategy, NRF UK would have to recruit 102 BAME staff, and no non-BAME staff, over the next five years.

This would give NRF UK annual growth in their workforce, in this period, of 1.6%.

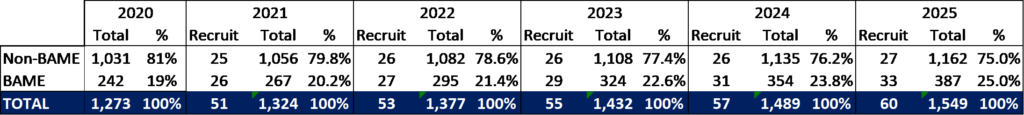

Strategy #3 – maximum growth

Of course, NRF UK may well have ambitions to grow their staff numbers by more than 1.6% annually, even in the straitened times many see ahead of us. Let’s look at a target for an annual growth of 4% in staff numbers (again, hitting the target on, but not before, schedule).

So, while the overall growth in numbers does mean a slight increase in annual recruitment of non-BAME staff, more than 50% of recruitment in the next five years will be of BAME staff. This chart shows this more clearly.

These figures are subject to many caveats, the biggest of which is I’ve not factored in any attrition. I think we can say that any attrition of BAME staff in this period will simply make the consequent replacement recruitment even more skewed to BAME staff. I could also have stepped the recruitment figures slightly less linearly, but it won’t make any difference to the end picture.

My conclusion, and the whole point of this blog, is to emphasise that in committing to growing the proportion of BAME staff in their UK workforce from 19% to 25% in the next five years, NRF (and firms pursuing similar targets) are committing themselves to significant targets for BAME recruitment in the UK – in NRF’s case, somewhere between 53% and 100% of all recruitment (assuming a cap on the growth of total staff numbers of 4% per annum) in the next five years.

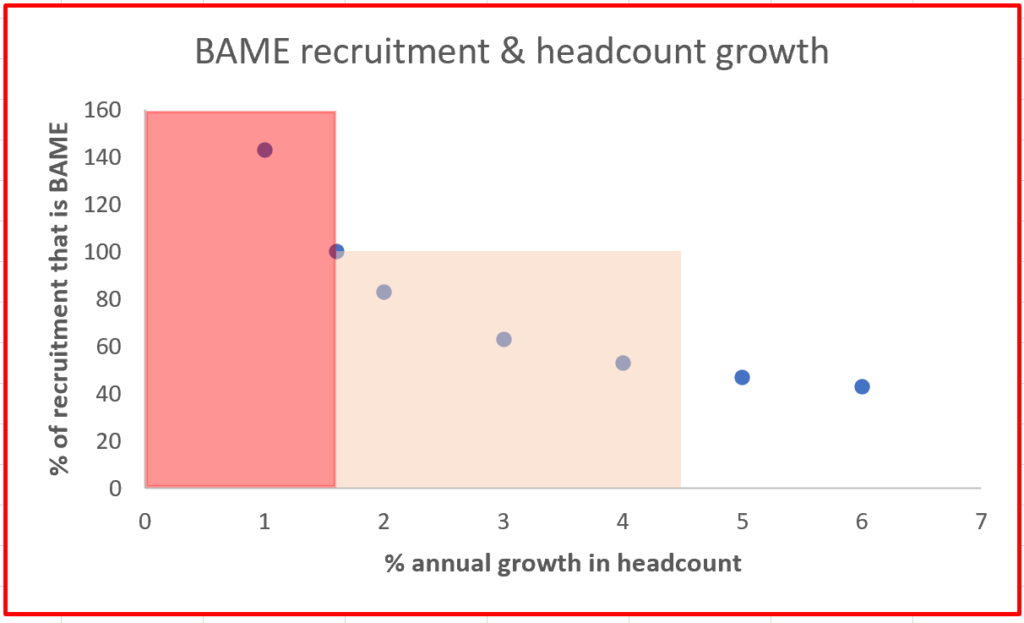

Even if NRF could get annual staff growth to 6%, they would still have to recruit 43% BAME. The graph below shows the impact of the headcount growth on the BAME recruitment goals.

In short:

- until annual headcount growth reaches 1.6 % (the pink area), NRF can only meet their UK target by shedding non-BAME staff; and

- until annual headcount growth reaches 4.4% (the salmon area), NRF will have to recruit more BAME staff than non-BAME to meet their UK target.

The real challenge for NRF and other firms pursuing similar targets is that only around 14% of the UK population are classified as BAME. The good news for NRF is that this figure rises to 40% in London (which is where their UK office is). But this still makes NRF’s targets ambitious and far more challenging than a casual look at their objectives might suggest.

The good news for BAME lawyers, paralegals and others who want to work in a UK law firm is that there may well be a war for their talent over the next five years.

Partner targets

The UK partner figures are equally interesting. Although the numbers look smaller (8% to 15%), the task NRF is setting itself is of a similar scale to that related to its workforce generally.

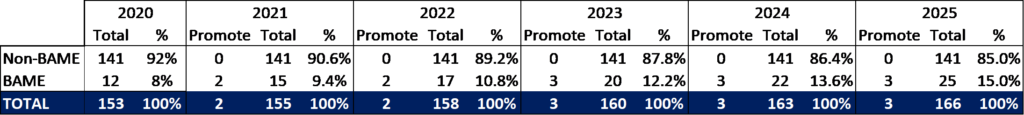

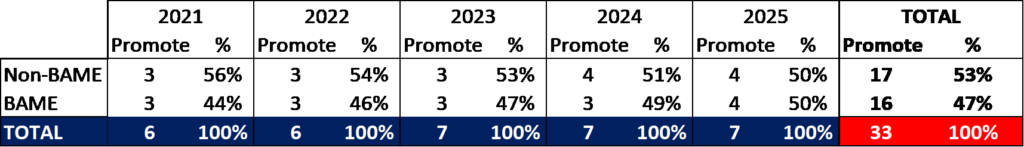

Again, we will contrast a “minimum” and a “maximum” strategy, and assume that partner numbers stay at a constant proportion of total workforce numbers. If NRF simply decide to grow BAME numbers in the UK so that by the end of the target period they have hit the target proportion, and assuming some sort of linear growth towards the target proportions, the promotion (including lateral external recruitment) targets will look something like this.

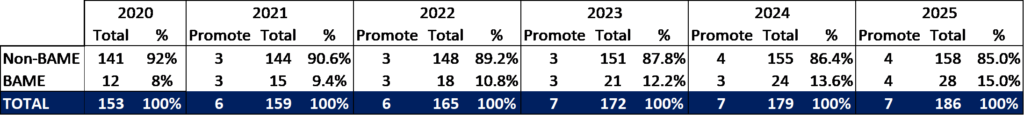

Again, this gives an annual growth rate of around 1.6%. If the annual target was as high as 4%, then the figures would look something like this:

The implications for partner promotions by ethnicity, with 4% annual headcount growth, can be more clearly seen in this chart.

The implications are very similar to those for the workforce as a whole:

- it will require annual headcount growth of at least 1.6% to hit the UK partnership target by 2025, and that will require 100% BAME promotions;

- the more annual headcount growth exceeds 1.6%, the more the required proportion of BAME promotions decreases, but even at 4% growth it is still at 47%

- external lateral recruitment of partners will require NRF to fish in an increasingly competitive market for BAME partners, and internally will probably require some acceleration of BAME lawyers.

Again, this is all good news for BAME lawyers.

My overall point has been to demonstrate that figures that might not look particularly challenging (from 19% to 25%, from 8% to 15% etc) actually mask some very ambitious recruitment objectives and strategies.

We have seen that, in effect, NRF is committing to a five-year plan in which somewhere between 50% and 100% of all UK recruitment will be of BAME staff. They are also committing to a promotion plan in which at least 45%, or so, and possibly significantly more, of all partner promotions in the next five years in the UK will be of BAME lawyers.

I would imagine the next challenge for D&I teams in UK firms is how to overlay these targets with other targets for, say, gender, disability, etc., and then how to avoid the trap of recruitment and promotion by simple quota. But that is for another day.

For now, I think we can say that the announcement of these targets is far more than mere sound and fury, and signifies a massive commitment, by one firm, to the recruitment and promotion of BAME lawyers and staff over the next five years in the UK.

All of us should wish them well in this ambition, and its execution.

Photo credits: documents icon (below) by Richard Copley; featured image (top) by Clay Banks on Unsplash